Pro basketball and football showed that tough rules work, but now the leagues are giving up.

About the author: Jemele Hill is a contributing writer at The Atlantic.

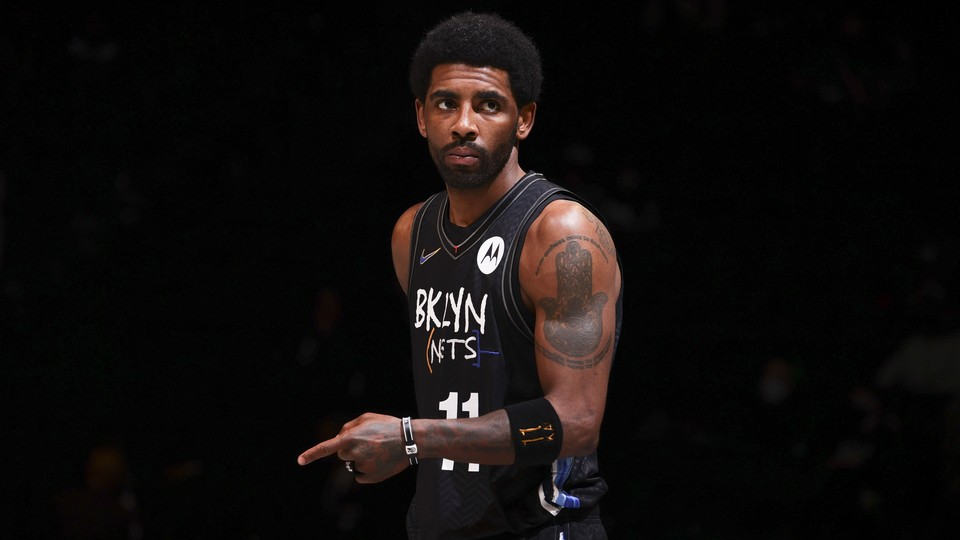

The Brooklyn Nets have officially ended their tug-of-war with Kyrie Irving over the star point guard’s vaccination status. And Irving, who has refused to get a COVID-19 shot, is unquestionably the winner.

The rapid spread of the coronavirus’s Omicron variant has left gaps on rosters across the NBA. Because positive tests had rendered so many players ineligible, the Nets finally buckled to Irving, who had not played this season because New York City’s vaccine mandate for certain indoor facilities had banished him from home games. To let Irving on the court now, even just for away games, is a drastic turnaround for a team that had sidelined him rather than deploy him part-time. After he cleared the NBA’s COVID-19 protocols on Tuesday, Irving will be eligible to play for the Nets when they travel to Indiana to face the Pacers on January 5.

This resolution of the Nets’ high-profile dispute with Irving is part of a larger problem in professional sports: Confronted with this latest virus surge, both the NBA and the NFL have essentially waved the white flag. They are easing their health rules and sending conciliatory signals to players who have refused to get COVID-19 shots.

Both leagues had adopted a range of health protocols that strongly encouraged vaccination. But now the leagues are choosing instead to cede to the forces of capitalism. Short-term financial concerns are dictating that even as Omicron spreads, games must go on. And if that means holding vaccinated and unvaccinated players to the same standards, the leagues will do it.

After the CDC issued new guidelines Monday that will shorten quarantine times for anyone who tests positive for the coronavirus, the NBA announced that players who test positive will have to isolate for only six days, rather than 10, if they have no symptoms. The NFL and the NFL Players Association quickly announced that players with positive test results can return after five days. Stunningly, the two leagues’ abbreviated new quarantine timelines apply to both vaccinated and unvaccinated players.

Until now, the NFL had rightly made a point of imposing additional burdens on unvaccinated players. For example, unvaccinated players had to undergo daily testing and, when the team traveled, could not fraternize with anyone but team personnel. These rules reflected the greater risk that unvaccinated players pose to others. The rules also created strong incentives: Among NFL players, the policy helped produce a vaccination rate of more than 94 percent—far higher than the rate for all American adults. (The rate for NBA players is even better: at least 97 percent.)

Some of these incentives are still in place. And earlier this month, the NFL suspended the Tampa Bay Buccaneers wide receiver Antonio Brown for three games because he brought a fake vaccination card to training camp. But the league started tinkering with its protocols after 150 positive cases turned up in mid-December. With the NFL playoffs looming, this was certainly a convenient time for the league and its health experts to devise ways of getting infected players back on the field faster. Under the old protocols, the Indianapolis Colts’ unvaccinated quarterback, Carson Wentz, who tested positive for the virus earlier this week, would not have been eligible to play against the Las Vegas Raiders this Sunday. Now, with the reduced quarantine time, Wentz can take part in a game that could clinch a playoff berth for his team.

The NFL and NBA aren’t exactly hiding their hand here. They are in the business of keeping business going. The Nets had seven players ineligible under the NBA’s health-and-safety protocols heading into the team’s marquee Christmas Day matchup against the Los Angeles Lakers. Among those left out was superstar forward Kevin Durant, who has since been cleared to play. The Nets have the best record in the Eastern Conference and a legitimate chance to win an NBA championship. Bringing Irving back will lighten the load on Durant—his playing time of 37 minutes per game ranks second in the league—as the NBA enters the meat of its season. And if another COVID surge comes over the team, Irving’s return means one more superstar is available for road games.

As of this week, the NBA has used 541 players this season—a league record. That’s because so many teams had to scramble to sign players to 10-day contracts to compensate for the staggering number of players on the COVID list. Despite that outrageous figure, neither the NBA nor the NFL were ever going to mimic the NHL, which decided to pause its season last week to deal with the surge in virus cases. (To compensate, the NHL also decided to pull its players from the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing to make them available for rescheduled games in February if necessary.)

The NFL and NBA’s latest protocol adjustments are just an extension of what’s going on elsewhere in the economy. The CDC’s decision to shorten quarantine times came six days after Ed Bastian, the CEO of Delta Air Lines, sent a letter begging the agency to reduce the isolation period for those who contracted the virus. Commercial aviation has been hit especially hard by the Omicron surge. Personnel shortages caused by positive tests have caused the cancellation of thousands of flights during a busy holiday season. According to The Washington Post, top health officials decided to reduce quarantine times because they feared far too many essential workers would otherwise be unable to work and industries would be crippled. Yet the new CDC breakthrough-infection guidance—which recommends the same isolation period for unvaccinated and vaccinated people and asks neither to get a negative test before ending their isolation—was even more permissive than many business leaders and sympathetic public-health experts had urged.

From that standpoint, it’s hard to blame the leagues for following a murky, complicated path. However, the shame is that these revised standards show that unvaccinated people will ultimately pay no penalty for adding so much chaos. Anti-vaxxers and right-wingers deemed Irving a martyr for his stance against vaccine mandates, and now he’ll get to play on his terms. As long as Wentz remains asymptomatic, Wentz will get to play, despite not doing his part to end this pandemic. Brown is back on the field and wants the public to forget that he selfishly jeopardized the safety of everyone around him because he lacked the discipline to adhere to the stricter protocols for unvaccinated players.

In the end, the NBA’s and NFL’s policies have emphasized two things—keeping fans entertained and keeping teams and athletes working. The players who have refused vaccines now know that, regardless of the disruption they have contributed, the desire to keep revenue flowing is on their side.