Dr. A.S., ND, PhD Issues Warning about the Summer of Lyme

Unprecedented Outbreak of Lyme Disease Predicted for 2017/2018

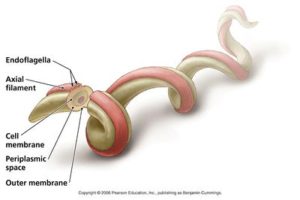

Borrelia burgdorferi

Borrelia burgdorferi

[Note from Ralph Fucetola, JD: “I received this warning from a naturopathic nutritionist of my acquaintance, compiling information from several sources. I asked him to let me pass on the warning, and he graciously allowed me to do so.”]

It’s an old but true saying: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Being aware of your health risks is an important step toward dealing with them. I want you all to be especially careful this summer of 2017.

According to an article written by AARP, experts warn that a bumper crop of acorns could be putting the US on the brink of an unprecedented outbreak of Lyme disease. With an estimated 300,000 of Americans diagnosed with Lyme disease each year, the illness is now on track to being the worst in 2017. The acorn surge means mouse populations will climb — giving rise to more disease-carrying ticks.

“We predict the mice population based on the acorns and we predict infected nymph ticks with the mice numbers. Each step has a one-year lag,” Rick Ostfeld told New Scientist magazine.

One mouse can carry hundreds of immature ticks, and that is a conservative estimate. The rodents’ blood contains the Lyme-causing bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which gets transferred to the tick’s stomach as it feeds. The bacteria can then be passed on to whatever new host — like humans — the tick latches onto.

With no Lyme disease vaccine available — the last one, Lymerix, was yanked off the market in 2002 due to safety concerns — what can be done to prevent the illness outside of the standard anti-tick measures, including wearing long pants in the woods and performing thorough self-checks?

You need to make sure that your immune system is supercharged and ready to fight Lyme or the other tick-borne diseases. Wholesome food, plenty of rest, exercise and nutrition are your key to surviving the Summer of Lyme. Nutritional supplementation, as I have always reminded my clients, is essential for a vibrant immune system.

Ticks are tiny, as small as a poppy seed, and easy to miss, and not everyone gets the bulls-eye rash that usually accompanies a Lyme-infected tick bite. The flu-like symptoms that occur after being infected are also easy to misdiagnose.

“That’s when you get late-stage, untreated, supremely problematic Lyme disease,” Ostfeld said.

Lyme disease diagnoses could soon soar globally, too. Researchers in Poland discovered the same acorn trends last year.

“Last year we had a lot of oak acorns, so we might expect 2018 will pose a high risk of Lyme,” Jakub Szymkowiak from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland, told New Scientist.

An explosion in the mice population across the northeastern United States is a worrying sign of a potentially similar-sized surge in cases of Lyme disease.

But people get Lyme disease from ticks, not mice, right? Deer are often blamed for being carriers of Lyme disease, infecting the ticks who feed on them, who then jump on to human hosts. But mice are among the most effective carriers of the condition, infecting 95 percent of the ticks who feed on them, according to NPR. Two biologists told NPR that they have found in mice a leading indicator of future Lyme outbreaks: the bigger the annual mouse population, the larger the following year’s pool of new Lyme cases will be. Once found primarily in the New England (the disease is named for Lyme, Connecticut), and a slice of Wisconsin, Lyme is now found all over the United States.

Its rise results in part from rising deer populations, but also in the changing landscape of the country. Land development for farming, housing and commerce has chewed through the once vast forests and wild lands of the U.S., leaving smaller patches of forest interspersed with human settlements. Mice thrive in these smaller forests, in large part because the larger animals who prey on them cannot. Reported cases of Lyme have tripled since the 1990s to 30,000 a year, but health officials think the real number could be ten times that, noted NPR.

Lyme is getting ready to explode, according to a researcher in New York State.

“We expect the risk of coming into contact with a tick harboring Lyme disease will be higher in 2017 than in the average year, probably along large parts of the Appalachian Trail,” said Rick Ostfeld, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y.

In the past, the federal Centers for Disease Control have estimated that about 300,000 people a year have Lyme disease. Holly Ahern, associate professor of microbiology at the State University of New York Adirondack, said that current diagnostic testing detects only about 50 percent of those who have the disease, and that the real number of annual cases is closer to 700,000.

“This means that for every two people who have Lyme disease, only one person will be diagnosed as having it. This leaves the other 50 percent without a diagnosis, and therefore without effective treatment,” Ahern said. “It is not just the fastest growing vector-borne disease, it is already the second most common infectious disease, right after chlamydia and ahead of gonorrhea.”

Lyme disease is spread by wood ticks. Because the 2015 season led to a bumper crop of acorns, the mice that are the wood ticks’ hosts are having a population boom, making it likely that 2017 will show an increase over past years.

One mouse can carry hundreds of immature ticks. The rodents’ blood contains the Lyme-causing bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. When the tick feeds on a mouse, it acquires the bacteria. It then passes that along to its next host, leading to Lyme disease in humans.

A Lyme disease vaccine was marketed in the late 1990s but was withdrawn in 2002 after lawsuits alleging that it was linked to the development of arthritis.

That leaves prevention as the best remedy. Standard prevention measures include wearing long pants and long sleeves in the woods as well as being thorough in examining legs and arms after being out in the woods. Supporting a vibrant immune system is an essential preventative step.

In its early stages, the symptoms of Lyme disease mimic the flu, which often leads to the wrong diagnosis.

“That’s when you get late-stage, untreated, supremely problematic Lyme disease,” Ostfeld said. Most but not all victims of a tick bite will see a red splotch where they were bitten that morphs into something resembling a bull’s-eye target. Without treatment, flu-like symptoms, including aches and fever, can follow. Untreated Lyme disease can lead to chronic joint inflammation, facial palsy, problems with short term memory, heart rhythm irregularities, and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord.

Experts say this summer could see a record increase in this Lyme Disease in broad regions of the Northeast and upper Midwest.

Last summer a plague of mice carrying Lyme-infested ticks inundated New York’s Hudson Valley — the epicenter for the illness. For Lyme researchers Felicia Keesing and Richard Ostfeld, that was a harbinger of bad things to come this year, as NPR.org recently reported.

Keesing, an ecologist at Bard College in Annandale, N.Y., specializing in tick-borne diseases, and her husband, Richard Ostfeld, a disease ecologist with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., have been studying Lyme disease for more than 20 years. Their prediction technique for the next year’s Lyme outbreak is simple: Count the number of mice in the current year. The higher the number, the worse the next outbreak will be.

That means the flood of mice last summer portends a big spike in illness this summer. “I’m sorry to say that’s the scenario we’re expecting,” Ostfeld told NPR.

Lyme disease is transmitted to humans through bacteria from the bite of an infected black-legged tick (also called a deer tick). The ticks, about the size of a poppy seed, cling to grasses and plants and attach themselves to people as they brush by. The ticks then burrow in hard-to-see places, like behind the ears and in the armpits and groin area.

Once the bacteria enter a person’s bloodstream, they can cause fever, fatigue, headache, joint pain and rashes. If not treated early enough with antibiotics (natural or pharmaceutical, your choice), Lyme can attack the circulatory and nervous system, causing severe muscle pain, irregular heartbeat and cognitive problems.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracks the number of reported Lyme cases in the U.S., which has tripled in the last few decades to about 30,000 cases annually, although one CDC epidemiologist told NPR she thinks the actual number is closer to 300,000, including unreported cases.

Learn about health discoveries, explore brain games and read great articles like, “18 Quirky Summer Health Tips’ in the AARP Health Newsletter.*

In 2015, 95 percent of confirmed Lyme cases were reported from 14 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and Wisconsin. If you live in these areas, it’s not just hiking and camping that can expose you to ticks. The CDC reports that most people get Lyme while walking or gardening around their house.

Here’s how to protect yourself:

- Check yourself every day for ticks if you live in a Lyme state. Don’t forget to check the places they like to hide, including behind the ears, on the scalp, and the armpits and groin. This CDC site also has helpful information about treatment, the blood test for Lyme disease and other useful tips.

- Dry your clothes before washing. If you’ve been outside, take off your clothes and throw them in the dryer on high heat for at least 20 minutes. Washing, even in hot water, won’t help kill ticks (the little suckers won’t drown), but baking them in a hot dryer will do the trick.

- If you find a tick, use tweezers and squeeze it by the head, not the body, to remove it.

Squeezing the body “will cause the tick to spew all of its stomach contents into the skin, and you’ll be more likely acquire whatever infection that tick was carrying,” Lyme expert Brian Fallow, M.D., director of the Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research at Columbia University Medical Center, told NPR.

- Beware bare skin. Don’t make it easy for ticks to bite you. Wear long-sleeved tops, long pants, socks and sturdy shoes when tromping through forested areas. Use repellents with DEET (or natural alternatives) on exposed skin and clothing.

- Seek treatment early. If you think you may have been bitten, be on the lookout for a red rash that slowly gets larger — sometimes resulting in a bull’s eye shape — as well as flu-like symptoms and joint pain. If you start to have any of these symptoms, don’t wait to see a doctor.

The sooner treatment gets started, the better your chances of recovery.

According to the Mayo Clinic, you can decrease your risk of getting Lyme disease with some simple precautions:**

- Cover up

- Use insect repellents

- Do your best to tick-proof your yard.

- Check yourself, your children and your pets for ticks

- Don’t assume you’re immune

- Remove a tick as soon as possible with tweezers (making sure that you remove it from the head)

To those good recommendations I would add, pay attention to your health. Rest, good food and nutritional supplementation will prepare your body for the risks of the Summer of Lyme.

—————

**Lyme disease Prevention- Mayo Clinic. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lymedisease/basics/prevention/con-20019701