Strict pandemic measures were already debunked years ago. So why did we use them for COVID?

‘Experience has shown that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted.’

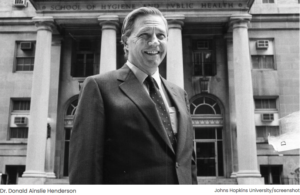

(Brownstone Institute) – Donald Henderson, who died in 2016, was a giant in the field of epidemiology and public health. He was also a man whose prophetic warnings from 2006 we chose to ignore in March of 2020.

Dr. Henderson directed a ten-year international effort from 1967–1977 that successfully eradicated smallpox. Following this, he served as Dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health from 1977 to 1990. Toward the end of his career, Henderson worked on national programs for public health preparedness and response following biological attacks and national disasters.

In 2006, Henderson and his colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Health Security, where Henderson also maintained an academic appointment, published a landmark paper with the anodyne title, “Disease Mitigation Measures in the Control of Pandemic Influenza,” in the journal Biosecurity and Terrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science.

This paper reviewed what was known about the effectiveness and practical feasibility of a range of actions that might be taken in attempts to lessen the number of cases and deaths resulting from a respiratory virus pandemic. This included a review of proposed biosecurity measures, later utilized for the first time during COVID, such as “large scale or home quarantine of people believed to have been exposed, travel restrictions, prohibitions of social gatherings, school closures, maintaining personal distance, and the use of masks.”

Even assuming a case fatality rate (CFR) of 2.5%, roughly equal to the 1918 Spanish flu but far higher than the CFR for COVID, Henderson and his colleagues nevertheless concluded that these mitigation measures would do far more harm than good.

They found the most helpful strategy would be isolating symptomatic individuals (but not those who had merely been exposed) at home or in the hospital, a strategy that had long been part of traditional public health.

They also cautioned against reliance on computer modeling to predict the effects of novel interventions, warning that, “No model, no matter how accurate its epidemiologic assumptions, can illuminate or predict the secondary and tertiary effects of particular disease mitigation measures.”

Furthermore, “If particular measures are applied for many weeks or months, the long-term or cumulative second- and third-order effects could be devastating socially and economically.”

Regarding forced quarantines of large populations, the authors noted, “There are no historical observations or scientific studies that support the confinement by quarantine of groups of possibly infected people,” and they concluded,

“The negative consequences of large-scale quarantine are so extreme (forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.”

Likewise, they found, “Travel restrictions, such as closing airports and screening travelers at borders, have historically been ineffective.” They argued that social distancing was also impractical and ineffective.

The authors noted that during previous influenza epidemics, large public events were occasionally cancelled; however, they found no evidence “that these actions have had any definitive effect on the severity or duration of an epidemic,” and they argue that “closing theaters, restaurants, malls, large stores, and bars… would have seriously disruptive consequences.” The review presented clear evidence that school closures would prove ineffective and enormously harmful. They likewise found no evidence for the utility of masks outside the hospital setting.

Henderson and his colleagues concluded their review with this overriding principle of good public health: “Experience has shown that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted.”

Needless to say, we did not heed any of this advice in March of 2020. We instead forged ahead with lockdowns, masks, social distancing, and the rest. When faced with COVID, we rejected time-tested principles of public health and embraced instead the untested biosecurity model. We are now living in the aftermath of this choice.

Source:

https://www.lifesitenews.com/opinion/strict-pandemic-measures-were-already-debunked-years-ago-so-why-did-we-use-them-for-covid/

One thought on “But It Was Never About Health, Was It?”