ANTONY BARNETT: DICHRON INTERVIEW

Paul D. Thacker, December 14th, 2021

Last Friday, the UK’s Channel 4 Dispatches released “Vaccine Wars: Truth About Pfizer.” While only half an hour in length, the documentary covers a wide space of ground. Pfizer’s contract with the British government is a carefully guarded secret, but what is known is that the company is charging Brits more than anyone else on the planet for each jab. This contrasts with AstraZeneca, which partnered with Oxford University to sell the vaccine not for profit. Dispatches also interviews whistleblower Brook Jackson, whom I featured in a BMJ investigation that examined data integrity problems in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical trial.

The documentary also uncovers new accusation against Pfizer: the funding of speakers who spread disinformation about AstraZeneca’s vaccine. In several talks to Canadians, speakers with ties to Pfizer alleged that AstraZeneca’s vaccine could cause cancer.

To get some insight into this documentary, The DisInformation Chronicle called up Dispatches reporter Antony Barnett. Barnett has been doing investigative documentaries for Dispatches for almost 15 years. Prior to this, he ran investigations for the Observer. “We were very worried that this program would be used in any way as a kind of a weapon for the anti-vaccine movement,” Barnett told The DisInformation Chronicle. “But in the end, you have to be willing to ask these types of questions.”

DICHRON: I really love the way you start, with this great quote from Tom Frieden, who’s the former Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): “If you’re just focusing on maximizing your profits, and you’re a vaccine manufacturer, you are war profiteering.”

I’ve also been thinking of the money these pharma companies make on these vaccines as war profiteering, but felt I might be going over an edge if I tweeted that. So I was stunned to hear it from the former CDC Director.

BARNETT: When we were doing the interview, I was stunned. It’s such a strong claim by someone in his position. He was very angry.

At the end of our documentary, I asked him if he had a message to Dr. Albert Bourla of Pfizer. And he started pointing his finger at me and accusing the company of war profiteering, while denying technology to countries that could save millions of lives.

DICHRON: You contrast Pfizer with AstraZeneca, which partnered on their vaccine with Oxford University. Oxford’s Andrew Pollard describes AstraZeneca as wanting a vaccine that was not for profit, “because it means it could be accessed everywhere at the lowest possible price.”

American universities are highly focused on profiting from intellectual property rights. But Oxford was so against this.

BARNETT: I think this was a very special case. AstraZeneca doesn’t often develop drugs and sell them for not-for-profit prices. Oxford University came to the decision that they would only go into bed with a drug company if they were going to do it not-for-profit. And AstraZeneca agreed that, in a time of a pandemic, that was the right thing to do.

Now they’re talking about earning a modest profit.

DICHRON: You also interview Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky, who’s been very critical of the drug industry in the United States. Here’s what she said about the pharmaceutical industry, “They had no intention whatsoever to make those prices more affordable or in any way to limit their profit.”

BARNETT: Pfizer’s vaccine is viewed largely as a national success story. There’s now increasing questions being asked about the profits. I saw the hearing where she interrogated the drug industry, and I was really struck by her passion, and you could see them equivocating and not quite sure what to say.

DICHRON: Here’s some interesting numbers you guys came up with about Pfizer. Revenue increased 130% in the third quarter of 2021; COVID vaccine revenue expected to be $36 billion, which is the largest increase for any drug in history. Some predict that next year this will be $55 billion, which is the GDP of Croatia.

These are eye popping numbers for something that is a public health issue.

BARNETT: You expect people to make reasonable profits. This is not about not making money. It’s just that these are massive numbers.

Someone described it as an epoch windfall, and I think that’s a right way to describe it.

DICHRON: Revenues don’t really tell you how much money you’re actually making, because any product requires investments. But you interviewed one expert who said Pfizer got an 80% gross profit margin, although Pfizer says it’s only 20%.

BARNETT: Because of the S.E.C., Pfizer has to be open about the revenues that come in. It’s much harder to work out the actual profit margins on the vaccine. Experts say it’s brilliant piece of revolutionary technology, but actually it’s pretty cheap to make.

We commissioned an expert in bioengineering, who basically spends all his time modeling manufacturing facilities for vaccine production, and we asked him how much it would cost to make four billion doses of this. His estimate was $1.05 as the most likely cost per dose.

Another person in the States told us it was going to cost about two or three dollars to make. That gives you a high gross margin of over 80%, which he said is not unusual in the drug industry.

DICHRON: You guys did a really good job of pointing out that Pfizer has been saying that they didn’t take any government money. Which is true. But their partner BioNTech got millions from Germany and the EU.

BARNETT: Yes, around half a billion—might be a bit more, might be a bit less. But just from the figures that we looked through, we reckon it was at least $500 million that BioNTech got.

DICHRON: As you were reporting for this documentary, did you see this explained properly in news articles when Pfizer would make these comments about how they hadn’t taken any money?

BARNETT: No. This vaccine is largely known as a Pfizer vaccine. BioNTech has been forgotten. It’s now called the Pfizer jab.

The honest answer is Pfizer made a lot of play about how they didn’t get money from Operation Warp Speed, which was the American policy of investing in the vaccines. But the original invention, the development of it, was inspired by BionTech, and that was largely with public money.

But this is rarely mentioned.

DICHRON: And while the AstraZeneca jab is much cheaper, the British government, is paying 22 pounds per jab for Pfizer—up from 18 pounds of this summer. Brits are paying even more than Americans, and it’s unheard of that any country pays more than America, because we have the highest pharma prices on the planet.

BARNETT: You kind of knew that the wealthier countries would pay the highest prices. But I was surprised when it emerged that the British government pays the highest price. I think Taiwan actually might be paying a bit more.

The actual price the government pays is a closely guarded secret. The government doesn’t want people to know about it, nor do the drug manufacturers. But the government hasn’t denied this and Pfizer hasn’t denied this.

DICHRON: How do you feel that your country is paying more than the Americans?

BARNETT: I’ve done a number of documentaries on the British government’s handling of the pandemic and there’s a number of areas that they can be criticized for being incompetent. But Pfizer holds all the bargaining power on these vaccine contracts. We put in a lot of early orders for vaccines, and Pfizer knew how important it was for the British government to get these vaccines.

For all we know, the government may have talked them down from a higher number. That’s why we need transparency, because it’s really hard to know what happened.

After Brexit, I did a program about a possible trade deal between the U.K. and America. And the drug companies were angry about NICE—an agency that negotiates drug prices for the National Health Service. During talks about this trade deal, the pharma companies wanted these secret arbitration panels which we now know are part of the vaccine contract between Pfizer and the British government. And that contract is highly redacted.

I’ve never seen such a redacted contract. One of the key reasons for Brexit was taking back control of the British courts. And now we’re giving the courts away to the US drug companies with these secret arbitrations.

DICHRON: You guys did a great job bringing in Brook Jackson, the whistleblower who exposed the problems in Pfizer’s clinical, whom I wrote about for The BMJ.

BARNETT: I want to put on the record that The BMJ did an amazing job. A lot of people involved in scientific research realize that to ensure public trust in medicine and drugs, it’s so important these clinical trials are conducted properly.

DICHRON: I was interviewed by a British radio program about that investigation, and what I told them was, “You get the government you pay for.” Brook Jackson brought credible allegations about Pfizer’s clinical trial to the FDA and they never investigated. I’m sure that if you look into that further, what you’re going to find out is that the FDA doesn’t have the appropriate funding to look into all these problems.

BARNETT: I guess what I didn’t fully appreciate is the scale of financial incentives involved and how this might play a part in cutting corners to hit targets for these clinical trial contractors.

DICHRON: When I interviewed other people who had worked at Ventavia with Brook Jackson, what they kept telling me was it’s all about money, and the clinical trial needs to be fast, fast, fast. Whoever gets their vaccine approved first has a huge market share. I hadn’t thought about that until it was explained to me.

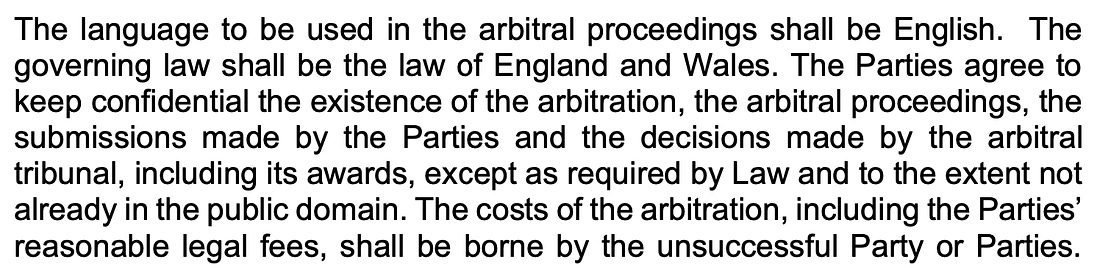

You also uncovered this program in Canada, with presentations being given to public health specialist saying that the AstraZeneca vaccine could cause chromosomal integration and possibly lead to oncogenesis—meaning it causes cancer. Speakers for a company running a disinformation campaign on a corporate competitor really shocked me.

BARNETT: We were passed those presentations, and they were given to pharmacists and physicians in Canada.

The key one was this claim that the AstraZeneca vaccine could potentially turn a healthy human cell into a cancer cell. These presentations were funded by Pfizer and were largely putting forward the benefits of the mRNA vaccine. What’s interesting is how that information got into the hands of people who were presenting it to doctors and pharmacists in Canada.

Those presenters were being paid by Pfizer or had received funds from Pfizer in the past. Pfizer, of course, denies it had anything to do with the materials.

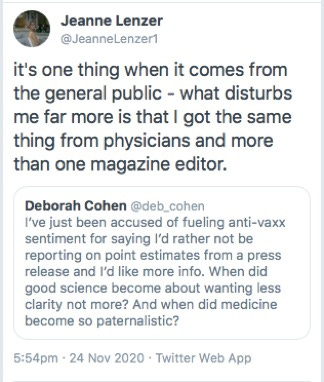

DICHRON: There’s been this drumbeat in which if you ask any questions about vaccines, then you’re labeled anti-vax. Deb Cohen with the BBC tweeted about this, some time back, as did Jeanne Lenzer with The BMJ.

Were you worried about that?

BARNETT: We were very worried that this program would be used in any way as a kind of a weapon for the anti-vaccine movement. In fact, the company that made it put out a special on the anti-vaccine movement.

But in the end, you have to be willing to ask these types of questions. People have died from having an AstraZeneca vaccine, on extremely rare occasions. We can’t cover that up. We have to explain how rare it is, and then look at the risks of the virus. With the Pfizer vaccine, it’s known that there’s a risk of myocarditis, that it’s more prevalent in young boys. You can’t be a journalist if you just hear that information and don’t ask questions. You’ve just got to report it and handle it responsibly.

These vaccines look like they’re going to be part of our lives for a long time, particularly with new variants coming along. And there’s a commercial interest to boost people, to give it to young kids—they’re talking about a fourth dose now. That might be a really important tool in controlling the virus.

But journalists should be asking the question, “Hold on. What’s the scientific basis for saying that a booster for a healthy 18-year-old is the best use of NHS money?” That might be a great decision, but you have to ask the question.

Sir Andrew Pollard said that as a healthy over 50-year-old, he would rather his third vaccine be given to a health worker in an African country. So we’ve got to be able to ask these questions without fear of being accused of being anti-vax.

Source: disinformationchronicle.substack.com/p/reporters-expose-pfizer-misinformation